|

Afterlife Reflection by Jerry Moyar ‘57 November 2, 2009 “I don’t want to be ashes,” said my young son, as he looked down at his shining little body in the bath tub. What do you say to a four year old? Even now my life-long friend writes : “I still pray to God but cannot believe in Christianity . . . Yes, I’m afraid we could be wrong and that we will rot in hell; just a belief in God is not enough.” Clearly he’s in some existential anguish. How can I help? Are the Final Judgment, heaven and hell real? What happens to us when we die? Those are some of the questions our classmate, Bishop Frederick Borsch’57, addresses in his provocative book, The Spirit Searches Everything – Keeping the Questions. (2005) In this Reflection, I’ll use Fred’s concept of “Divine Awareness,” developed in his book, to explore similarities and differences among several contemporary writers on this issue, with special attention to Princeton connections. I’ll close with a confession of sorts on what I believe. I will not attempt a treatise on the history and evolution of beliefs in the afterlife. I’m certainly not up to it, and you can readily find other comprehensive and authoritative sources on that. I will be concerned primarily with the beliefs of contemporary thinkers (most I admire) whose books I have read, have heard speak on more than one occasion, and have had a chance to talk to, however briefly in certain instances. And as a life-long friend told me, I don’t want to disturb those secure in their faith. In recent decades much has been written about the afterlife, after the three-story world view passed on for most of us. It seems to all depend on the reality and character of God -- believed in or experienced. I direct this discussion primarily to those who don’t accept the traditional theistic understanding of God as an external personal being who intervenes from time to time and passes judgment on humanity. Instead I’ll be guided by the thinking of three progressive former bishops I know, Fred Borsch ‘57, John Shelby Spong, and Richard Holloway – something like a “Three Tenors” performance review. Other ‘singers’ will be noted along the way. For many, if not all, the starting point is our evolved human self-consciousness and self-awareness. The Three Bishops Our classmate Bishop Fred Borsch ‘57 offers what he calls a “riff” on the afterlife in the last chapter of The Spirit Searches Everything: Keeping Life’s Questions . ‘Riff’ is an apt term for ideas he shares, since he recognizes that improvisation in music and poetry provides the best expression of religious concepts, including afterlife. The book is based on his development of the idea of human awareness. “Out of that mammalian brain in far more developed ways through the human neocortex, appears a consciousness of what is happening.” ( p.7) Fred then builds on the concept of “Divine Awareness,” often employing poetry – his and others – to further refine his thought. Such Awareness is alternatively called “Divine Spirit.” This “. . . Awareness may be moving from a future into which all are drawn. Everything of value is preserved in this way – saved by being taken into the Awareness and the compassion of God.” (p. 132) A “glorious intuition,” (p. 134) he calls it. The book closes with a recounting of some fundamental questions on the meaning of life and our awareness leading to “What happens to our awareness at death?” He answers, “A faith that responds, ‘Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . . you are with me’ trusts that our awareness continues to be valued in God’s. God then, as the saying goes, isn’t finished with us yet. God isn’t finished with all God’s hope. Indeed, by this hope we may only have begun to be the people the Spirit of God wishes us to be. But in the context of the divine Awareness of all life we may believe that we have begun, and, in this Spirit, find a sense of questing adventure for now and all that is to be.”( p. 138) Thus it appears that Fred believes in some sort of afterlife in the “Spirit,” despite his acknowledgment that, “As amazing as it is for a brain with billions of neurons and trillions of synaptic junctions to come into existence, as remarkable as is the capacity for awareness to transcend self and to love, the switchboard operator goes with the switchboard. The software dies along with the hardware.” (p. 128) John Shelby Spong is the former Episcopal Bishop of Newark, prolific writer and speaker – often controversial. I was the target of a rather nasty in-your-face protest on one occasion as I walked into a church to hear him speak. Most times it’s just hostile questions or accusations from one or two in the audience directed at the bishop. In a small group discussion I once asked Spong how to get through to hard line fundamentalists. He answered directly, “You can’t.” Spong’s statement, “I will seek God apart from religion.” Eternal Life: A New Vision – Beyond Heaven, Beyond Theism, Beyond Heaven and Hell. (2009), (p.135) does not endear him even to the more polite ones in the congregation. His most recent book, Eternal Life: A New Vision . . . . (the last, claims this near octogenarian) recounts the development throughout his life of his own position on the topic in a way similar to Fred Borsch. (Who said “all good theology is really autobiography”?) He writes, “The dramatic step from consciousness to self-consciousness occurred not too long ago, relatively speaking” (p.27) – then from self-consciousness into self-awareness. Finally he recognizes “an entirely new understanding of life – that is, a new awareness was certainly not a new reality. We have always been a part of that which is greater than we are. Is it not, therefore, reasonable to assume that we just might always have been a component of the greater reality?” (p.146) “There is something about human life that escapes time’s boundaries and experiences timelessness.” (p.147) After the struggle to picture God as either person or process, he acknowledges that “We stretch and groan against the limitations of language [when] we seek to crack through our limits in order to reach or find a new perception of all that is. When we travel that road, will we see this journey as an invitation to walk in a state of awareness which eternally is, and to which we belong? . . . We had to walk through self-consciousness to discover the universal consciousness. We had to walk through the time-bound to discover the timeless. That was necessary before we could claim our identity as part of who God is.” (p.155) His “universal consciousness” echoes Borsch’s Divine Awareness. Finally, with his experience and understanding of God, he concludes with his answer to Job’s question so long ago – “ ‘If a man [or a woman] dies, will he [or she] live again?’ – my answer would be yes, yes, yes!’’ (p.212) Bishop Richard Holloway retired as Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church. His writings reflect an evolution in his faith over the past decade from a point in between traditional belief and a-theism. In an article in the Westar Institute’s Fourth R magazine of November – December, 2000, “Charge to the Synod of the Diocese of Edinburgh,” he addressed the question: “Is there an originating reality behind the universe that transcends and sustains it?” He answered that he is in the middle between non-realism (no reality outside the mind) and critical realism (reality relative to time and place). I once asked him that if someone called him a Christian humanist, would they be far off the mark? He answered simply, “no.” By the time of the Westar Spring meeting in New York in 2004 he said offhandedly: “I’ve spiraled all the way down.” The militant atheist, Richard Dawkins, reports in his God Delusion (2006) that Holloway stated in a Guardian book review: “I’m a recovering Christian.” Where is he now? The final chapter of Holloway’s book, Looking in the Distance – The Human Search for Meaning (2004) reveals his negative view of eternal life as commonly believed. “Paul Celan taught us, at our beginning, to praise Nothing for the brief joy of life. Now, at our ending, we can praise Nothing for the blessed oblivion into which we shall return.” (p.212) He selects as the last poem of many in his book, ‘Aubade’ by Philip Larkin. The ending lines are: ‘Who shall make them afraid Who saw eternity In the brief compass of an April day?’ (p.214) His book closes with,“So we shall live the fleeting day with passion and, when the night comes, depart from it with grace.” (p.215) Other Biblical Scholars Marcus Borg holds the Hundere Chair in Religion and Culture at Oregon State University. A fellow of the Jesus Seminar, he was president of the Anglican Association of Biblical Scholars. He is a sought after speaker in churches around the world. Borg is a colleague of John Dominic Crossan, and with him has coauthored several books, among them The Last Week – What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem (2006). Although sharing some of Spong’s ideas, Borg is better accepted among traditional church groups. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that his wife is an Episcopal priest. In a Washington Post Internet article of October 10, 2007 he writes, “I am a committed Christian and a complete agnostic about the afterlife.” Yet, later he says, “What I do affirm about what happens after death is very simple: When we die, we do not die into nothingness, but we die into God. In the words of the apostle Paul, we live unto the Lord and we will die unto the Lord. So whether we live or die, we are the Lord’s.” John Dominic Crossan is Emeritus Professor of Biblical Studies at DePaul University in Chicago, and a preeminent scholar of the historical Jesus. Crossan is one of my heros. In his short Q&A book coauthored with Richard Watts for lay people, Who is Jesus ? (1996), he responds in his usually succinct way to a frequent question asked by lay people, “Do I personally believe in an afterlife? No, but to be honest, I do not find it a particularly important question one way or the other. I am not in the least bit interested in fighting those who believe or hope in it. My own interest is in how we live our lives here below.” (p.131) Lloyd Geering is Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at Victoria University, New Zealand, honored as a Principal Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2001. He survived a heresy trial unscathed in the Presbyterian church there. He is what he has termed a non-theistic Christian. I’ve heard this quick-witted and charming man speak on two occasions. He caused a public uproar about 42 years ago in New Zealand when he preached a sermon on Ecclesiastes in which he agreed with the writer that “we are mortal creatures who have no immortal souls . . .” and later in his book, “The [Israelite] sages had always affirmed the complete mortality of the human condition, as did Israel as a whole. . . “ (Christianity without God 2002, pp.113 - 115) In one of his many books, Life, Life (2003), Don Cupitt, a teacher of religion at Cambridge University, has a brief comment on the afterlife: “. . . there is no life after death . . . The rational response is to forget about death, and simply to concentrate our attention upon life now. Instead of dreaming about a heaven beyond the grave, we should seek to ‘eternalize’ our life in the here and now. When we have learnt to find eternal happiness in the present moment, we will no longer lament the loss of a rather questionable prospect of it hereafter.” (p.121) Despite his views on the “hereafter,” Cupitt is a humanist with a spiritual side. He is the ‘father’ of the “Sea of Faith” movement started in Great Britain inspired by by a BBC TV series and a book (1984) of the same title. The movement takes its name from the well known poem, ‘Dover Beach,’ by Matthew Arnold. Cupitt was ordained ‘deacon’ (priest) in the Church of England in 1960. As recently as the 2004 Westar Spring meeting in New York, I heard him make this side comment about church ritual, “God help me, I love it so.” Some “Far Out” Thinkers Most of us know something about Deepak Chopra, a frequent TV interviewee and popular author of dozens of books on all things spiritual with a mystical East Indian twist. I have read only one of his books, so I cannot claim a real understanding of his philosophy. Yet I think his ideas are pertinent in the context of this Afterlife Reflection because some of them touch on the same self- awareness and Divine Awareness themes encountered above. In Life After Death (2006), Chopra claims that, “Consistently polls show that 90% of people believe in heaven, and almost that many believe they are going there. Belief in hell suffers a sharp decline to 75% and only 68% believe in the devil.” (p.194) Chopra sees death as a door to continuing life, but in the cyclic sense of reincarnation into a development of successor beings. Finally the soul passes into an all encompassing spirit, the Dharma, when true enlightenment is reached. Like Borsch he starts with consciousness or “self-awareness.” Therefore, Chopra believes in survival of the mind after the brain is dead. Or, alternatively, in life after life. Chopra describes a wide range of traditions and studies on afterlife, including the Vedic wisdom tradition, parapsychology, neurology, and the ‘spooky’ domain of the quantum field, to establish the opening for the next life. It is particularly interesting to me that Chopra bases his rationale in part on the research and ideas of two Princeton professors; the late Princeton physics professor John Wheeler and engineering professor Robert Jahn. The implications of these two men’s ideas are sketched below. I remember a beautiful spring day at Princeton in 1954 when Prof. Wheeler took our small physics class of Freshmen outside to discuss Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. I was quite puzzled and said so. How could an observer possibly influence one aspect of a subatomic particle/wave (say position) while measuring or simply observing another aspect (say momentum)? – even if we don’t interfere physically and just observe through a ‘hands-off’ window of objectivity? Prof. Wheeler was patient with me but left me still puzzled and reexamining my basic assumptions. Perhaps a frequently quoted statement attributed to Wheeler’s famous student, Richard Feynman, is true: “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” Beside the concept of the “geon” gravity particle, still evolving in his mind then, Wheeler’s honest and warm demeanor communicated the excitement of science that never left us. I believe he also proposed, on a cosmological level, the concept of a “Big Crunch” leading to a cyclic Universe. It’s difficult to accept that this great man passed away from us so recently (April of 2008).

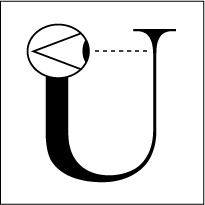

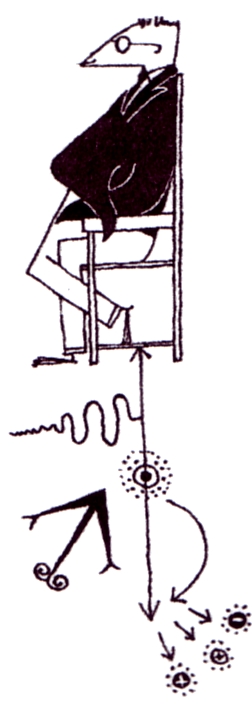

Wheeler also created a symbol of the self-aware universe, or “participatory universe,” which is often used by others in various fields of science, philosophy and religion. The U stands for the universe, and the eye for observers who evolve, and then look back at the origin. Is there a way we can look back and recreate Prof. Wheeler? Frank J. Tipler is Professor of Mathematical Physics at Tulane University who wrote The Physics of Immortality - Modern Cosmology, God and Resurrection of the Dead (1994). Tipler asserts that theology is now, as result of his Omega Theory, a branch of physics. He acknowledges that Wheeler was his mentor (p. 169), but makes no other mention of Wheeler except to call the Wheeler-DeWitt wave function “superfluous.” (p. 177) In his book he develops the so-called Omega Point Theory in ‘logical scientific’ detail. At the peak of Universe expansion life is everywhere ‘emulated’ in the form of super-intelligent computers before it ultimately collapses into the Omega Point or “Big Crunch” at the end of time – or something like that. Although I have checked the book out on two occasions, I honestly have not been able to make any headway through it. He claims, in an “Appendix for Scientists,” that to comprehend the science behind his theory would require Ph.D.s in “at least three disparate fields” (global general relativity, theoretical particle physics, and computer complexity theory). It all seems bazaar to me but Graham Oppy, an Australian professor of philosophy of religion, is one who has taken Tipler seriously, writing that any science graduate student would be able to understand Tipler’s Omega Point Theory and it’s flaws. He then proceeds to ‘demolish’ the theory. Go to www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Frank-Tipler for his critical review. “A large majority of his colleagues in physics consider his logic to be flawed . . ..”– so says StateMaster Encyclopedia. My wife, Ruth, reminded me of the poem “The Theory Jack Built” in the classic, The Space Child’s Mother Goose (1958), verses by Frederick Winsor and Illustrations by Marian Parry. The illustration shown here is the one accompanying early lines in that poem: “This is the Flaw That lay in the Theory Jack built.”

The poem ends with: This is the Space Child with brow Serene Who pushed the Button to Start the Machine That made with the Cybernetics and Stuff Without Confusion, exposing the Bluff That hung on the Turn of a plausible Phrase And, shredding the Erudite Verbal Haze Cloaking Constant K Wrecked the Summary Based on the Mummery Hiding the Flaw And Demolished the Theory Jack built.” Would Prof. Wheeler have actually agreed? Robert G. Jahn was Professor and Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Princeton. His special research project, the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research, PEAR, investigated experimentally the effect of an observer’s intentions on shifting the mean of the distribution of random events. After nearly three decades PEAR has concluded its experimental operations at Princeton, claiming that it did succeed in proving a small but statistically significant effect of ‘mind over matter’ (on a large scale). It has now shifted its base of operations to the International Consciousness Research Laboratories (ICRL). I’ve asked our classmate, Fred Borsch, who was Professor of Religion and Dean of the Chapel at Princeton during some of Jahn’s research: how could such research continue so long at Princeton, and what was faculty and Administration reaction? Fred was generous in speaking of Prof. Jahn, whom he knew from friendly conversations in which Jahn tried to convince him of his conclusions – without success, I gathered. Fred said there was, in fact, little faculty interest in PEAR, and it survived because of the spirit of academic freedom there. A recently published book by the conservative political speaker and lately Christian apologist, Dinesh D’Souza, Life After Death: The Evidence (2009) was the subject of an article, “Heaven Can Wait,” by Jerry Adler, contributor to Newsweek magazine, published in a recent issue. (November 9, 2009) Adler points out D’Souza’s dependence on anecdotal near death experiences, references to quantum mechanics and parallel universes, as part of his indirect ‘evidence.’ D’Souza certainly falls into the category of “Far Out” Thinkers. In a peculiar twist, he asserts that the universally-acknowledged Problem of Evil is solved in a parallel universe where compensation for innocent suffering and punishment of evil is meted out – thus proving the existence of a good God and the afterlife. Still mourning the death of his young son, Adler makes it clear where he stands: “Is there any comfort in the idea that Max lives on as a disembodied consciousness in a parallel universe? I want him here with me now, and would gladly trade my prospects for Eternity for the chance to hug him once more.” (To understand where D’Souza ‘comes from,’ see Princeton Alumni Weekly, Vol. 109, No. 7 for an account of D’Souza’s debate last December with Princeton professor and bioethicist Peter Singer on “morality without God.”) Some Humor In a Pocket Guide to the Afterlife, (2009), Jason Boyett brings easy humor to the otherwise serious topic of afterlife, while providing a worthwhile assembly and definition of beliefs in many scriptures, through the ages and around the globe. As an example (picked almost at random): “Spirit Prison – What it is: The Mormon hell, also known as ‘outer darkness.’ Very few people are wicked enough to end up there forever – most go to one of the three degrees of glory known as the Celestria, Terrestrial, and Telestrial Kingdoms – but those who do go to Spirit Prison are known as ‘sons of perdition.’ Which would be an excellent name for a bluegrass band (Live Tonight from Provo: Donny Osmond & the Sons of Perdition!).” (p. 120) Richard Holloway also uses humor (sometimes pointed) to illustrate a concept. In discussing reincarnation and its belief that how we live in this incarnation determines our future births, he observes, “ . . . in the future re-incarnation of souls, no memory of the previous life seems to be passed on; so that a dung beetle’s life is not disfigured by memories of his previous career as, say, the Governor of Texas.” (Doubts and Loves, (2001) p. 99). A hilarious You Tube video was brought to my attention by one of my sons: “Lust is the Beast within YOU!!!” with actor Wallace Shawn. In it FatherAbruzzi (Shawn) sternly admonishes students at a Catholic school dance regarding sex. See www.youtube.com/watch?v=iA_SstpZOlY. Google the title and Shawn to find other locations. What do I Think? What do I think about death and the prospect of life after that – whether in heaven, hell, or simply extinction? Truthfully, it has not really troubled me (yet, at any rate) and I have not given it much thought until now, despite my being on death’s doorstep a couple of times. On those occasions during long stays in Intensive Care Units I was a bit disappointed that I didn’t experience an out-of-body revelation of the sort that Elizabeth Kubler-Ross wrote about in her classic book (On Death and Dying (1969)). I’ve already been given more good life than anyone could have expected almost twenty-three years ago. So I’m grateful for the life I’ve had, and will pass into oblivion without regrets. That’s not quite right. Sometimes I do have regrets about not being able to see how my grandchildren, friends and loved ones live their future lives. I take comfort in knowing that I join my ancestors and all living things in the end – in either extinction or whatever else may be in store. What did I say to my young son in the tub? Nothing very meaningful, for certain. I think it was just something along the lines of, “Oh don’t worry about that. You have so much good life ahead of you to live.” While this was an impromptu and not very profound comment, in light of some of the conclusions of authors above about afterlife, it seems I am in good company. What did I write to my cousin? “It really pains me to learn you are in so much distress over this afterlife and hell business. First, my belief in this matter is not academically based. Second, not all people who are Christians follow Jesus because of a fear of hell. Finally, can you imagine that a merciful God would consign 2/3 and more of the world's population to eternal damnation because they don't believe church doctrine or are ignorant of it? That would include the best and most compassionate people -- like Mahatma Gandhi, or the innocent child born into another religious culture.” I have no expectation of an afterlife, but I’m not as “principled” about it as the character in the story that is told to Ivan in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (First Signet Classics printing 1958, p.744) by a strange “gentleman” (Satan?). In that story a “thinker and philosopher,” who rejected everything, died and “expected to go straight to darkness and death and he found a future life before him. He was astonished and indignant. ‘This is against my principles!’ ” Finally, what about those innocents whose life on earth has been a hell, or those evildoers who prosper? Is there no compensation or fairness? Haven’t these concerns been the genesis of the hope of afterlife, in addition to the inclination to secure and maintain ecclesiastical power and control? What do you think about the afterlife?

Acknowledgments: Although I take full responsibility for these personal views, I was helped by discussions with family and friends. These included specifically: Inspiration and questions from my life-long; a reminder on Holloway’s humor from Nan Reitz W‘57; discussions with my sons, Jim, Jess, and Tim – especially Jess’ emphasis on “timelessness;” funny videos from both Jess and Tim, and helpful graphics from Tim. Finally, as usual, my wife Ruth helped turn my very rough drafts into English and eliminate my most banal and obscure passages. Afterlife Reflection by Jerry Moyar ‘57 November 2, 2009 “I don’t want to be ashes,” said my young son, as he looked down at his shining little body in the bath tub. What do you say to a four year old? Even now my life-long friend writes : “I still pray to God but cannot believe in Christianity . . . Yes, I’m afraid we could be wrong and that we will rot in hell; just a belief in God is not enough.” Clearly he’s in some existential anguish. How can I help? Are the Final Judgment, heaven and hell real? What happens to us when we die? Those are some of the questions our classmate, Bishop Frederick Borsch’57, addresses in his provocative book, The Spirit Searches Everthing – Keeping the Questions. (2005) In this Reflection, I’ll use Fred’s concept of “Divine Awareness,” developed in his book, to explore similarities and differences among several contemporary writers on this issue, with special attention to Princeton connections. I’ll close with a confession of sorts on what I believe. I will not attempt a treatise on the history and evolution of beliefs in the afterlife. I’m certainly not up to it, and you can readily find other comprehensive and authoritative sources on that. I will be concerned primarily with the beliefs of contemporary thinkers (most I admire) whose books I have read, have heard speak on more than one occasion, and have had a chance to talk to, however briefly in certain instances. And as a life-long friend told me, I don’t want to disturb those secure in their faith. In recent decades much has been written about the afterlife, after the three-story world view passed on for most of us. It seems to all depend on the reality and character of God -- believed in or experienced. I direct this discussion primarily to those who don’t accept the traditional theistic understanding of God as an external personal being who intervenes from time to time and passes judgment on humanity. Instead I’ll be guided by the thinking of three progressive former bishops I know, Fred Borsch ‘57, John Shelby Spong, and Richard Holloway – something like a “Three Tenors” performance review. Other ‘singers’ will be noted along the way. For many, if not all, the starting point is our evolved human self-consciousness and self-awareness. The Three Bishops Our classmate Bishop Fred Borsch ‘57 offers what he calls a “riff” on the afterlife in the last chapter of The Spirit Searches Everything: Keeping Life’s Questions . ‘Riff’ is an apt term for ideas he shares, since he recognizes that improvisation in music and poetry provides the best expression of religious concepts, including afterlife. The book is based on his development of the idea of human awareness. “Out of that mammalian brain in far more developed ways through the human neocortex, appears a consciousness of what is happening.” ( p.7) Fred then builds on the concept of “Divine Awareness,” often employing poetry – his and others – to further refine his thought. Such Awareness is alternatively called “Divine Spirit.” This “. . . Awareness may be moving from a future into which all are drawn. Everything of value is preserved in this way – saved by being taken into the Awareness and the compassion of God.” (p. 132) A “glorious intuition,” (p. 134) he calls it. The book closes with a recounting of some fundamental questions on the meaning of life and our awareness leading to “What happens to our awareness at death?” He answers, “A faith that responds, ‘Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . . you are with me’ trusts that our awareness continues to be valued in God’s. God then, as the saying goes, isn’t finished with us yet. God isn’t finished with all God’s hope. Indeed, by this hope we may only have begun to be the people the Spirit of God wishes us to be. But in the context of the divine Awareness of all life we may believe that we have begun, and, in this Spirit, find a sense of questing adventure for now and all that is to be.”( p. 138) Thus it appears that Fred believes in some sort of afterlife in the “Spirit,” despite his acknowledgment that, “As amazing as it is for a brain with billions of neurons and trillions of synaptic junctions to come into existence, as remarkable as is the capacity for awareness to transcend self and to love, the switchboard operator goes with the switchboard. The software dies along with the hardware.” (p. 128) John Shelby Spong is the former Episcopal Bishop of Newark, prolific writer and speaker – often controversial. I was the target of a rather nasty in-your-face protest on one occasion as I walked into a church to hear him speak. Most times it’s just hostile questions or accusations from one or two in the audience directed at the bishop. In a small group discussion I once asked Spong how to get through to hard line fundamentalists. He answered directly, “You can’t.” Spong’s statement, “I will seek God apart from religion.” Eternal Life: A New Vision – Beyond Heaven, Beyond Theism, Beyond Heaven and Hell. (2009), (p.135) does not endear him even to the more polite ones in the congregation. His most recent book, Eternal Life: A New Vision . . . . (the last, claims this near octogenarian) recounts the development throughout his life of his own position on the topic in a way similar to Fred Borsch. (Who said “all good theology is really autobiography”?) He writes, “The dramatic step from consciousness to self-consciousness occurred not too long ago, relatively speaking” (p.27) – then from self-consciousness into self-awareness. Finally he recognizes “an entirely new understanding of life – that is, a new awareness was certainly not a new reality. We have always been a part of that which is greater than we are. Is it not, therefore, reasonable to assume that we just might always have been a component of the greater reality?” (p.146) “There is something about human life that escapes time’s boundaries and experiences timelessness.” (p.147) After the struggle to picture God as either person or process, he acknowledges that “We stretch and groan against the limitations of language [when] we seek to crack through our limits in order to reach or find a new perception of all that is. When we travel that road, will we see this journey as an invitation to walk in a state of awareness which eternally is, and to which we belong? . . . We had to walk through self-consciousness to discover the universal consciousness. We had to walk through the time-bound to discover the timeless. That was necessary before we could claim our identity as part of who God is.” (p.155) His “universal consciousness” echoes Borsch’s Divine Awareness. Finally, with his experience and understanding of God, he concludes with his answer to Job’s question so long ago – “ ‘If a man [or a woman] dies, will he [or she] live again?’ – my answer would be yes, yes, yes!’’ (p.212) Bishop Richard Holloway retired as Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church. His writings reflect an evolution in his faith over the past decade from a point in between traditional belief and a-theism. In an article in the Westar Institute’s Fourth R magazine of November – December, 2000, “Charge to the Synod of the Diocese of Edinburgh,” he addressed the question: “Is there an originating reality behind the universe that transcends and sustains it?” He answered that he is in the middle between non-realism (no reality outside the mind) and critical realism (reality relative to time and place). I once asked him that if someone called him a Christian humanist, would they be far off the mark? He answered simply, “no.” By the time of the Westar Spring meeting in New York in 2004 he said offhandedly: “I’ve spiraled all the way down.” The militant atheist, Richard Dawkins, reports in his God Delusion (2006) that Holloway stated in a Guardian book review: “I’m a recovering Christian.” Where is he now? The final chapter of Holloway’s book, Looking in the Distance – The Human Search for Meaning (2004) reveals his negative view of eternal life as commonly believed. “Paul Celan taught us, at our beginning, to praise Nothing for the brief joy of life. Now, at our ending, we can praise Nothing for the blessed oblivion into which we shall return.” (p.212) He selects as the last poem of many in his book, ‘Aubade’ by Philip Larkin. The ending lines are: ‘Who shall make them afraid Who saw eternity In the brief compass of an April day?’ (p.214) His book closes with,“So we shall live the fleeting day with passion and, when the night comes, depart from it with grace.” (p.215) Other Biblical Scholars Marcus Borg holds the Hundere Chair in Religion and Culture at Oregon State University. A fellow of the Jesus Seminar, he was president of the Anglican Association of Biblical Scholars. He is a sought after speaker in churches around the world. Borg is a colleague of John Dominic Crossan, and with him has coauthored several books, among them The Last Week – What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem (2006). Although sharing some of Spong’s ideas, Borg is better accepted among traditional church groups. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that his wife is an Episcopal priest. In a Washington Post Internet article of October 10, 2007 he writes, “I am a committed Christian and a complete agnostic about the afterlife.” Yet, later he says, “What I do affirm about what happens after death is very simple: When we die, we do not die into nothingness, but we die into God. In the words of the apostle Paul, we live unto the Lord and we will die unto the Lord. So whether we live or die, we are the Lord’s.” John Dominic Crossan is Emeritus Professor of Biblical Studies at DePaul University in Chicago, and a preeminent scholar of the historical Jesus. Crossan is one of my heros. In his short Q&A book coauthored with Richard Watts for lay people, Who is Jesus ? (1996), he responds in his usually succinct way to a frequent question asked by lay people, “Do I personally believe in an afterlife? No, but to be honest, I do not find it a particularly important question one way or the other. I am not in the least bit interested in fighting those who believe or hope in it. My own interest is in how we live our lives here below.” (p.131) Lloyd Geering is Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at Victoria University, New Zealand, honored as a Principal Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit in 2001. He survived a heresy trial unscathed in the Presbyterian church there. He is what he has termed a non-theistic Christian. I’ve heard this quick-witted and charming man speak on two occasions. He caused a public uproar about 42 years ago in New Zealand when he preached a sermon on Ecclesiastes in which he agreed with the writer that “we are mortal creatures who have no immortal souls . . .” and later in his book, “The [Israelite] sages had always affirmed the complete mortality of the human condition, as did Israel as a whole. . . “ (Christianity without God 2002, pp.113 - 115) In one of his many books, Life, Life (2003), Don Cupitt, a teacher of religion at Cambridge University, has a brief comment on the afterlife: “. . . there is no life after death . . . The rational response is to forget about death, and simply to concentrate our attention upon life now. Instead of dreaming about a heaven beyond the grave, we should seek to ‘eternalize’ our life in the here and now. When we have learnt to find eternal happiness in the present moment, we will no longer lament the loss of a rather questionable prospect of it hereafter.” (p.121) Despite his views on the “hereafter,” Cupitt is a humanist with a spiritual side. He is the ‘father’ of the “Sea of Faith” movement started in Great Britain inspired by by a BBC TV series and a book (1984) of the same title. The movement takes its name from the well known poem, ‘Dover Beach,’ by Matthew Arnold. Cupitt was ordained ‘deacon’ (priest) in the Church of England in 1960. As recently as the 2004 Westar Spring meeting in New York, I heard him make this side comment about church ritual, “God help me, I love it so.” Some “Far Out” Thinkers Most of us know something about Deepak Chopra, a frequent TV interviewee and popular author of dozens of books on all things spiritual with a mystical East Indian twist. I have read only one of his books, so I cannot claim a real understanding of his philosophy. Yet I think his ideas are pertinent in the context of this Afterlife Reflection because some of them touch on the same self- awareness and Divine Awareness themes encountered above. In Life After Death (2006), Chopra claims that, “Consistently polls show that 90% of people believe in heaven, and almost that many believe they are going there. Belief in hell suffers a sharp decline to 75% and only 68% believe in the devil.” (p.194) Chopra sees death as a door to continuing life, but in the cyclic sense of reincarnation into a development of successor beings. Finally the soul passes into an all encompassing spirit, the Dharma, when true enlightenment is reached. Like Borsch he starts with consciousness or “self-awareness.” Therefore, Chopra believes in survival of the mind after the brain is dead. Or, alternatively, in life after life. Chopra describes a wide range of traditions and studies on afterlife, including the Vedic wisdom tradition, parapsychology, neurology, and the ‘spooky’ domain of the quantum field, to establish the opening for the next life. It is particularly interesting to me that Chopra bases his rationale in part on the research and ideas of two Princeton professors; the late Princeton physics professor John Wheeler and engineering professor Robert Jahn. The implications of these two men’s ideas are sketched below. I remember a beautiful spring day at Princeton in 1954 when Prof. Wheeler took our small physics class of Freshmen outside to discuss Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. I was quite puzzled and said so. How could an observer possibly influence one aspect of a subatomic particle/wave (say position) while measuring or simply observing another aspect (say momentum)? – even if we don’t interfere physically and just observe through a ‘hands-off’ window of objectivity? Prof. Wheeler was patient with me but left me still puzzled and reexamining my basic assumptions. Perhaps a frequently quoted statement attributed to Wheeler’s famous student, Richard Feynman, is true: “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” Beside the concept of the “geon” gravity particle, still evolving in his mind then, Wheeler’s honest and warm demeanor communicated the excitement of science that never left us. I believe he also proposed, on a cosmological level, the concept of a “Big Crunch” leading to a cyclic Universe. It’s difficult to accept that this great man passed away from us so recently (April of 2008).

Wheeler also created a symbol of the self-aware universe, or “participatory universe,” which is often used by others in various fields of science, philosophy and religion. The U stands for the universe, and the eye for observers who evolve, and then look back at the origin. Is there a way we can look back and recreate Prof. Wheeler? Frank J. Tipler is Professor of Mathematical Physics at Tulane University who wrote The Physics of Immortality - Modern Cosmology, God and Resurrection of the Dead (1994). Tipler asserts that theology is now, as result of his Omega Theory, a branch of physics. He acknowledges that Wheeler was his mentor (p. 169), but makes no other mention of Wheeler except to call the Wheeler-DeWitt wave function “superfluous.” (p. 177) In his book he develops the so-called Omega Point Theory in ‘logical scientific’ detail. At the peak of Universe expansion life is everywhere ‘emulated’ in the form of super-intelligent computers before it ultimately collapses into the Omega Point or “Big Crunch” at the end of time – or something like that. Although I have checked the book out on two occasions, I honestly have not been able to make any headway through it. He claims, in an “Appendix for Scientists,” that to comprehend the science behind his theory would require Ph.D.s in “at least three disparate fields” (global general relativity, theoretical particle physics, and computer complexity theory). It all seems bazaar to me but Graham Oppy, an Australian professor of philosophy of religion, is one who has taken Tipler seriously, writing that any science graduate student would be able to understand Tipler’s Omega Point Theory and it’s flaws. He then proceeds to ‘demolish’ the theory. Go to www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Frank-Tipler for his critical review. “A large majority of his colleagues in physics consider his logic to be flawed . . ..”– so says StateMaster Encyclopedia. My wife, Ruth, reminded me of the poem “The Theory Jack Built” in the classic, The Space Child’s Mother Goose (1958), verses by Frederick Winsor and Illustrations by Marian Parry. The illustration shown here is the one accompanying early lines in that poem: “This is the Flaw That lay in the Theory Jack built.”

The poem ends with: This is the Space Child with brow Serene Who pushed the Button to Start the Machine That made with the Cybernetics and Stuff Without Confusion, exposing the Bluff That hung on the Turn of a plausible Phrase And, shredding the Erudite Verbal Haze Cloaking Constant K Wrecked the Summary Based on the Mummery Hiding the Flaw And Demolished the Theory Jack built.” Would Prof. Wheeler have actually agreed? Robert G. Jahn was Professor and Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Princeton. His special research project, the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research, PEAR, investigated experimentally the effect of an observer’s intentions on shifting the mean of the distribution of random events. After nearly three decades PEAR has concluded its experimental operations at Princeton, claiming that it did succeed in proving a small but statistically significant effect of ‘mind over matter’ (on a large scale). It has now shifted its base of operations to the International Consciousness Research Laboratories (ICRL). I’ve asked our classmate, Fred Borsch, who was Professor of Religion and Dean of the Chapel at Princeton during some of Jahn’s research: how could such research continue so long at Princeton, and what was faculty and Administration reaction? Fred was generous in speaking of Prof. Jahn, whom he knew from friendly conversations in which Jahn tried to convince him of his conclusions – without success, I gathered. Fred said there was, in fact, little faculty interest in PEAR, and it survived because of the spirit of academic freedom there. A recently published book by the conservative political speaker and lately Christian apologist, Dinesh D’Souza, Life After Death: The Evidence (2009) was the subject of an article, “Heaven Can Wait,” by Jerry Adler, contributor to Newsweek magazine, published in a recent issue. (November 9, 2009) Adler points out D’Souza’s dependence on anecdotal near death experiences, references to quantum mechanics and parallel universes, as part of his indirect ‘evidence.’ D’Souza certainly falls into the category of “Far Out” Thinkers. In a peculiar twist, he asserts that the universally-acknowledged Problem of Evil is solved in a parallel universe where compensation for innocent suffering and punishment of evil is meted out – thus proving the existence of a good God and the afterlife. Still mourning the death of his young son, Adler makes it clear where he stands: “Is there any comfort in the idea that Max lives on as a disembodied consciousness in a parallel universe? I want him here with me now, and would gladly trade my prospects for Eternity for the chance to hug him once more.” (To understand where D’Souza ‘comes from,’ see Princeton Alumni Weekly, Vol. 109, No. 7 for an account of D’Souza’s debate last December with Princeton professor and bioethicist Peter Singer on “morality without God.”) Some Humor In a Pocket Guide to the Afterlife, (2009), Jason Boyett brings easy humor to the otherwise serious topic of afterlife, while providing a worthwhile assembly and definition of beliefs in many scriptures, through the ages and around the globe. As an example (picked almost at random): “Spirit Prison – What it is: The Mormon hell, also known as ‘outer darkness.’ Very few people are wicked enough to end up there forever – most go to one of the three degrees of glory known as the Celestria, Terrestrial, and Telestrial Kingdoms – but those who do go to Spirit Prison are known as ‘sons of perdition.’ Which would be an excellent name for a bluegrass band (Live Tonight from Provo: Donny Osmond & the Sons of Perdition!).” (p. 120) Richard Holloway also uses humor (sometimes pointed) to illustrate a concept. In discussing reincarnation and its belief that how we live in this incarnation determines our future births, he observes, “ . . . in the future re-incarnation of souls, no memory of the previous life seems to be passed on; so that a dung beetle’s life is not disfigured by memories of his previous career as, say, the Governor of Texas.” (Doubts and Loves, (2001) p. 99). A hilarious You Tube video was brought to my attention by one of my sons: “Lust is the Beast within YOU!!!” with actor Wallace Shawn. In it FatherAbruzzi (Shawn) sternly admonishes students at a Catholic school dance regarding sex. See www.youtube.com/watch?v=iA_SstpZOlY. Google the title and Shawn to find other locations. What do I Think? What do I think about death and the prospect of life after that – whether in heaven, hell, or simply extinction? Truthfully, it has not really troubled me (yet, at any rate) and I have not given it much thought until now, despite my being on death’s doorstep a couple of times. On those occasions during long stays in Intensive Care Units I was a bit disappointed that I didn’t experience an out-of-body revelation of the sort that Elizabeth Kubler-Ross wrote about in her classic book (On Death and Dying (1969)). I’ve already been given more good life than anyone could have expected almost twenty-three years ago. So I’m grateful for the life I’ve had, and will pass into oblivion without regrets. That’s not quite right. Sometimes I do have regrets about not being able to see how my grandchildren, friends and loved ones live their future lives. I take comfort in knowing that I join my ancestors and all living things in the end – in either extinction or whatever else may be in store. What did I say to my young son in the tub? Nothing very meaningful, for certain. I think it was just something along the lines of, “Oh don’t worry about that. You have so much good life ahead of you to live.” While this was an impromptu and not very profound comment, in light of some of the conclusions of authors above about afterlife, it seems I am in good company. What did I write to my cousin? “It really pains me to learn you are in so much distress over this afterlife and hell business. First, my belief in this matter is not academically based. Second, not all people who are Christians follow Jesus because of a fear of hell. Finally, can you imagine that a merciful God would consign 2/3 and more of the world's population to eternal damnation because they don't believe church doctrine or are ignorant of it? That would include the best and most compassionate people -- like Mahatma Gandhi, or the innocent child born into another religious culture.” I have no expectation of an afterlife, but I’m not as “principled” about it as the character in the story that is told to Ivan in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (First Signet Classics printing 1958, p.744) by a strange “gentleman” (Satan?). In that story a “thinker and philosopher,” who rejected everything, died and “expected to go straight to darkness and death and he found a future life before him. He was astonished and indignant. ‘This is against my principles!’ ” Finally, what about those innocents whose life on earth has been a hell, or those evildoers who prosper? Is there no compensation or fairness? Haven’t these concerns been the genesis of the hope of afterlife, in addition to the inclination to secure and maintain ecclesiastical power and control? What do you think about the afterlife?

Acknowledgments: Although I take full responsibility for these personal views, I was helped by discussions with family and friends. These included specifically: Inspiration and questions from my life-long friend; a reminder on Holloway’s humor from Nan Reitz W‘57; discussions with my sons, Jim, Jess, and Tim – especially Jess’ emphasis on “timelessness;” funny videos from both Jess and Tim, and helpful graphics from Tim. Finally, as usual, my wife Ruth helped turn my very rough drafts into English and eliminate my most banal and obscure passages. |

|

| For additional information, contact the Webmaster Copyright © 2026, Princeton University Class of 1957 |